This put me in mind of an American client, Lydia, I saw recently. She’d initially written to me asking for a consultation about how autism affects family life. I was in two minds about whether to offer a consultation as I’d recently decided not to consult with people asking for advice about how to understand their autistic partner (more about this later), but accepted this as it was a more general request.

At the start of the consultation Lydia told me she’d worked with autistic children and she loved them and had loved her husband who “has Asperger’s” to bits. When she met him she was delighted by how well he got on with her (then 16 year old) son. Her son was now in his twenties and had recently got an Asperger’s diagnosis. As the details of her story accumulated it seemed increasingly likely to me that Lydia was also autistic.

In my experience a high percentage of autistic people have autistic partners even if only one partner identifies as autistic, autism runs in families so having an autistic son makes it likely that one or both of the parents are autistic, and people who are successful working with autistic people are often autistic themselves (and often initially unaware of it – I’ve had several such clients and we’ve had such people join AutAngel).

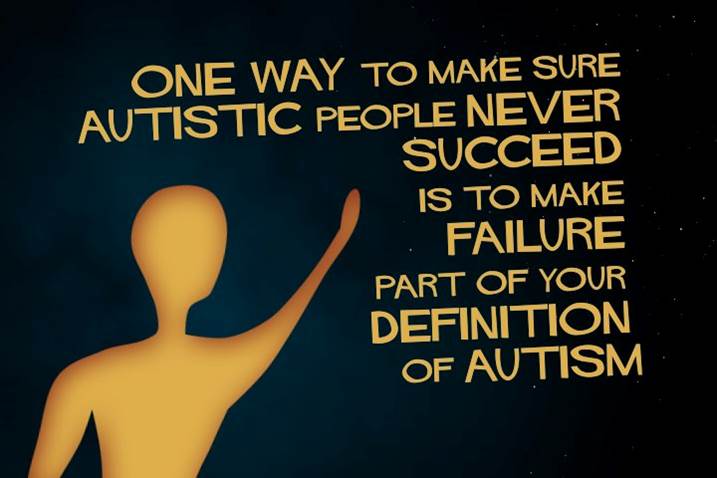

I was wondering whether to mention my impression. Suggesting someone might be autistic isn’t something I do casually as it is such a stigmatised condition that this can be experienced as a negative conclusion. On the other hand it has the potential to be immensely helpful. I made the judgement call to put this forward as a possibility. Lydia accepted this readily saying it was something she’d wondered about over the years. She told me about her school years where she was a grade A student, until she noticed how difficult it was to fit in, and then she switched all her attention to watching how other people behaved and learning to imitate them. She was reasonably successful at this but her school grades fell down radically.

She told me she was always outgoing and cheerful, but she had no idea who she really was. Her responses to other were performances rather than expressions of personality and she found human interaction tiring.. When I explained that autistic people had atypical developmental trajectories, and that we usually lack a sense officially called “theory of mind” but I call a “intuition of mind”. this all made sense to her and she expressed joy and gratitude at being presented with a reason for something she had never understood. There was still the issue of her husband’s increasingly inconsiderate and frankly unacceptable to behaviour to her. She told me when she tried to discuss things he would insist there was nothing to discuss as he felt OK, seemingly unaware that it was relevant whether she also felt OK.

Lydia had mentioned to her husband and some family members that she thought she might be autistic, but everyone denied this was possible, her mathematician husband saying this was inconceivable as she was diametrically opposite to him, and got on so well with people. (A feature of autistic people is that we inhabit the outer edges of the human constellation in all directions, so we are not alike, it is not unusual for people to be told they can’t be autistic because they are so different to a specific autistic person) At the end of a first session I always say to people that they can take some time to think if they would like to book further sessions and can let me know by email if they would, but Lydia wanted to book another session there and then (which isn’t that unusual), and paid that evening (which is unusual).

However when the time came for the next session I got a note thanking me for my support and saying she would not be attending as it was apparent that she wasn’t autistic and her feelings of being ‘sandwiched’ in between her ‘Aspie’ family members were correct. She needed to find someone who understood this.

I experienced this note as a shock that knocked the air out of me. Lydia had seemed so pleased to be given information that enabled her to contextualise her life experience and enabled her to feel less alone. I can only assume that this feeling dissipated when immersed in the larger societal understanding of autism as being other, such that it was only acceptable when seen as a problem in her family members that she needed to deal with rather than a part of herself.

My experience is that when women (and in my case it has been women) come to me saying they want consultations to help them understand their autistic (male) partners is that what seems to be wanted, albeit indirectly, is a way to blame problems in their relationship onto “autism” rather than to engage with the necessary compromise required by any ongoing relationship.

I no longer accept clients who request consultation for the purposes of understanding autistic partners, I instead refer them to training which they can attend with their partner (this is the most useful as they can discuss the contents together) or by themselves with the opportunity to interact with the mixture of autistic and non-autistic participants that my trainings attract

RSS Feed

RSS Feed