The stereotypes about autism result both in autism often being unidentified because the autistic person doesn’t fit them, and also in people not daring to suggest to others that they or a family member might be autistic as this is likely to be regarded as a negative label. It is often said that there are four times as many autistic men as autistic women, although it is finally being generally recognised that in fact women are underdiagnosed.

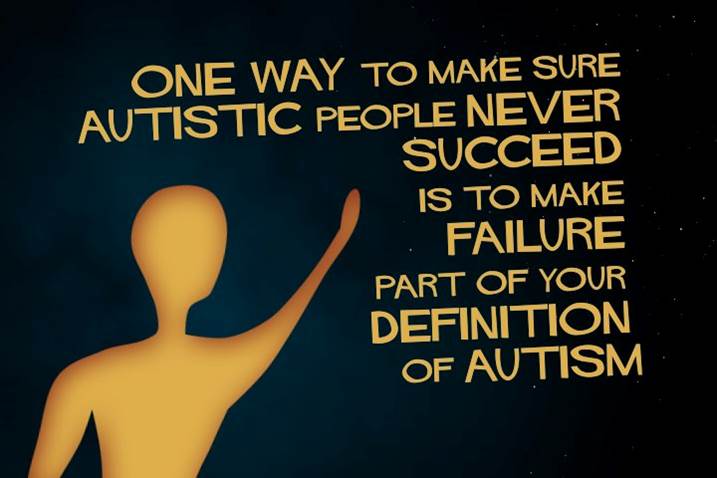

It seems to me that autistic people often choose, or find themselves with, autistic partners and this can happen even if neither party is aware of autism. Sometimes the realisation of autism comes once their child has been identified or diagnosed as autistic and the parent recognises that they are very similar to the child. Due to the negative views of autism that Langdon Bryce encapsulates in his cartoon, coming to this conclusion can be slow and painful. Sometimes people are willing to accept that a family member might be autistic but are much slower to recognise the autism in themselves. (It’s interesting that it’s acceptable to state categorically “I’m not autistic” without any diagnostic process, whilst some people think that only an accredited diagnostitian can tell if someone is autistic.)

Some time ago (before I was working in the autism field) I was talking to a neighbour, Martin, about his thirteen year old daughter Emma, whom I’d known since she was two. I knew that Emma was depressed and had been seeing the school counsellor. Martin told me how worried he and his wife were as things seemed to be getting worse, Emma was no longer seeing her friends and becoming increasingly isolated. She was feeling completely hopeless and indeed appeared suicidal. I wondered if in fact Emma had become depressed because she was isolated rather than the other way round. Autistic people often develop intellectually more quickly than we develop emotionally and socially. The social landscape changes rapidly for teenagers, and autistic young people often feel alientated and no longer able to connect with others in their age group in this new social environment.

I mentioned that Emma’s developmental trajectory - being intellectually precocious but then in adolecence starting to struggle socially-was something I’d seen in many autistic women and asked if it had occurred to Martin that this might be part of the picture. It hadn’t. Martin thanked me for my concern and asked me to email him some information about autism in girls and women. When I next saw him three weeks later I asked him if he’d got the information I’d sent. He told me he’d received it but hadn’t had time to look at it. If my child was suicidal I would be desperate to access any information that could be relevant and helpful. I was suprised and saddened that autism must have felt so aversive to Martin that he couldn’t consider it might apply to his daughter . (Later on his wife came to a training session about autism and appeared to accept that there was autism in the family. She took her daughter to a psychologist with a good understanding of autism and Emma recovered.)

Recently, I spent some time talking with a self-identified neurotypical woman about her autistic partner. She seemed concerned to understand his behaviour better and seemed happy with my responses to her situation and my suggested explanations for her husband’s behaviour. However when the possibility that she too may be autistic was raised, she told me how impossible that was as she was very emotional and that’s why she struggles so much to understand how her husband couldn’t get what came so easily to her. The suggestion that she might also be autistic was unacceptable to her and our conversations came to an end. I was sad about this for both of us; for her because I didn't see how her narrative could improve her relationship with her autistic husband and children, and for me because I worried that I'd unintentionally colluded with the idea that the problem in the relationship was located in her husbands neurology.

Over time, I’ve come across many couples where one partner is diagnosed or identified as autistic and the other partner also seems to be autistic but is not aware of this. Even (or perhaps especially) people who work in the field are vulnerable to this misreading. A case in point is the author, speaker and consultant Sarah Hendrickx of Hendrickx Associates who wrote a book about being a neurotypical person in a relationship with a man with Asperger's Syndrome before realising that she is herself autistic. Despite working in the autism field Sarah was totally unaware for years of her own autism. Ten years on from writing as a neurotypical partner, Sarah is now a proud out autistic woman. When I asked her if she minded being mentioned in this post as someone who feels her relationship is successful and endures because both she and Keith are autistic, she responded that she was happy to be quoted “it is entirely the case that we remain deliriously happy and deeply in love after 13+ years because we are both autistic in combination with our knowledge and tolerance of what we both need. Having a good autistic partner for me is like being able to breathe out in a world where I often feel like I'm holding my breath and know that someone can see all of who I am and will not judge or disapprove.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed