Potential Client (PC) I’m phoning because I’ve just found out I’m autistic and I’d like to get an some consultation, is that something you could do.

Me Yes, that’s exactly what I do I offer consultation sessions about autism, to discuss the impact of identifying as autistic and how autistic traits might impact on your life.

PC Good. So I’ll tell you some more about my situation. I’m working……….

Me Sorry can I stop you there, the way I work is that people book a time to talk with me and pay via the website and then we talk at the agreed time. We can book a time now and it would be confirmed when you pay.

PC Oh. If I’m consulting with a professional I expect to tell them something of what I require and then we decide if they’re suitable, I don’t expect to part with my money to a stranger before learning a bit more about them.

Me Yes, certainly, I’ve put a lot about myself on my website and I find that is enough for people to get an idea of my approach and if they think I might be suitable. To further see if they feel comfortable with me I ask that people book a session. It’s an investment I realise, but I do have a reduced rate for people who need it.

PC So you’re saying you want to end this conversation now.

Me That’s not how I would have put it, but the way I work is that I don’t have advance conversations with people. Consultations are not the only work I do and it wouldn’t work for me to interrupt my other work for initial chats with people before they consult with me.

PC So you want to end the conversation, I don’t want to end the conversation but you do.

Me As I say I wouldn’t have put it like that, and it seems to me this is the sort of approach that autistic people have that can create problems in life which is something we could discuss. As I say you can review my website and see if you feel I’d be suitable for you.

PC That’s not very professional of you. You have spent more time talking than listening that’s not how I expect a professional to behave.

Me Sorry that you find me unprofessional but you’re right I do want to finish the conversation and will end the conversation now.

I don’t think either of us covered ourselves in glory in this dialogue. The approach of PC reminded me of how I’d similarly hounded someone in a group many years ago to insist they say they didn’t like a project when that was neither their wording or something they wished to express in that way.

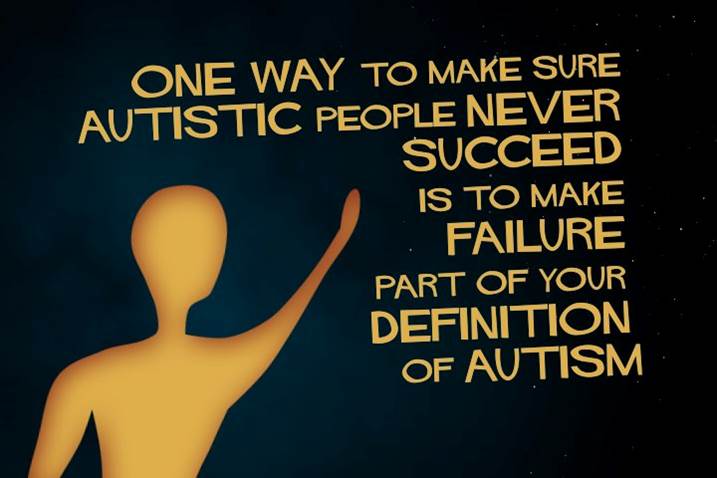

PC was right I did want to end the conversation however that was not the only relevant point and was not the one that I wished to share. Autistic people often can sense what others are feeling, and the lack of ability to sense what they might be thinking (misleadingly called theory of mind) can lead to interactions like this that are experienced negatively by all parties.

Neither PC nor I achieved our aims in this situation, in this case it was partly because the aims were irreconcilable – he wanted to explain his situation in detail and have someone listen and behave in the way he regarded as professional, and I wanted to have my lunch in peace and have a client who followed my usual protocol. However, this could have been handled better on both sides.

PC could have said “I see you don’t have advance conversations with people, that’s something I require so it sounds like you’re not the consultant for me” and I could have said “Yes you’re right, I do want to end this conversation now, but we can speak at greater length if you do check my website and choose to book a session”. …

However, my wish to justify myself and PC’s wish to be right overrode what was presumably a joint wish for a positive interaction and resulted in our unsatisfactory, but very autistic exchange.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed